There is a seismic shift taking place in the health care ecosystem with changing roles for everyone. In this transition to value-based and consumer-driven health care, there is a need to recognize the importance of non-medical causes of poor health such as poverty, access to healthy food, job skills, safe neighborhoods and healthy housing. Hospitals and clinics now are identifying ways to address these non-medical barriers to create improved health outcomes for patients. Greater patient engagement is a potential bi-product in this shift as health care providers build deeper relationships with patients and the conversation around health evolves.

External factors impact overall health

In a children’s hospital or clinic setting, when our patients and their families seek medical care, they often are facing additional critical challenges in their lives – they may have little food, they may not have a job or they may struggle to keep up with the bills for utilities. Unfortunately, these challenges often affect the health outcomes of children.

Multiple studies reveal that only 20 percent of positive health outcomes are attributed to medical care, while 20 percent can be linked to genetics. The biggest portion–60 percent–are based on social, environmental and behavioral factors. Therefore, if we truly want to improve the health of children we need to shift focus from their immediate health care into their environment and behaviors that impact health.

Real needs identified through trusted relationships

There is growing evidence that health improvement can be achieved by identifying the social determinants of health, targeting the families’ basic needs and directing appropriate resources to these children and their families within the health care system. The visit to a pediatric clinician offers a unique opportunity to have these vital needs identified. Clinicians have a trusted relationship with children and their parents which offers a chance to shine light on additional challenges a family may be facing. Through an appropriately designed screening process, the health care team can assist in addressing these health-related disparities that can contribute to long-term health outcomes.

The Family Resource Connection: A Social Needs Screening Program

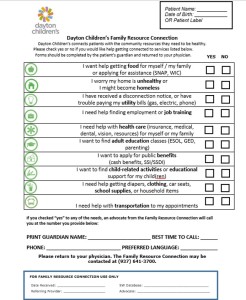

At Dayton Children’s Hospital, we are exploring this notion through the Family Resource Connection, a new social needs screening program. This program screens families for basic social needs as they check in for appointments. We have a simple screening tool which asks yes or no questions such as “I want help getting food for myself/my famil y or applying for assistance” or “I worry my home is unhealthy.” If a family identifies needs, the physician explains to the family that they will be contacted by an advocate in our Family Resource Connection. Within 48 hours, we reach out to patient families telephonically, work with them to identify their needs and then work to match community resources to those needs. Within the first few months of our program, we have found about 40 percent of families identify at least one social need.

y or applying for assistance” or “I worry my home is unhealthy.” If a family identifies needs, the physician explains to the family that they will be contacted by an advocate in our Family Resource Connection. Within 48 hours, we reach out to patient families telephonically, work with them to identify their needs and then work to match community resources to those needs. Within the first few months of our program, we have found about 40 percent of families identify at least one social need.

The program is modeled after the well-known and respected Health Leads, however we employ our own staff and recruit local students for referrals and follow-up. Because this program is part of the hospital system, we also provide clinical communication back to the physician–giving insight into the needs presented by the families and what we have done to address those needs.

Tangible Wins, Improved Health Outcomes

While we are only a few months into the program, early wins include families physically visiting our program because they have built a relationship with student advocates. We have been able to stop utilities from being shut off and have connected dozens of families to food pantries, school supplies and diapers. Over and over, we have found families appreciate someone asking them these questions and truly helping them navigate community resources.

Social needs screening and resource referral and follow-up may be a promising practice to extend patient engagement beyond the office visit. This and similar models may hold a key to engaging families in health – beyond healthcare – into the home, school, playground or neighborhood where health truly happens.