I consider myself one of the lucky ones. When I was diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer in 2009, I had a 40% to 50% chance of surviving five years. Now, 11 years later, not only am I alive, but as far as we know, I’m also cancer-free. So, now I’m lucky in more ways than one.

But it has taken me a lot of time to feel this lucky. And there have been many occasions, as I’ve lived into my “new normal,” where I have feared that my luck had run out. How many occasions, you ask?

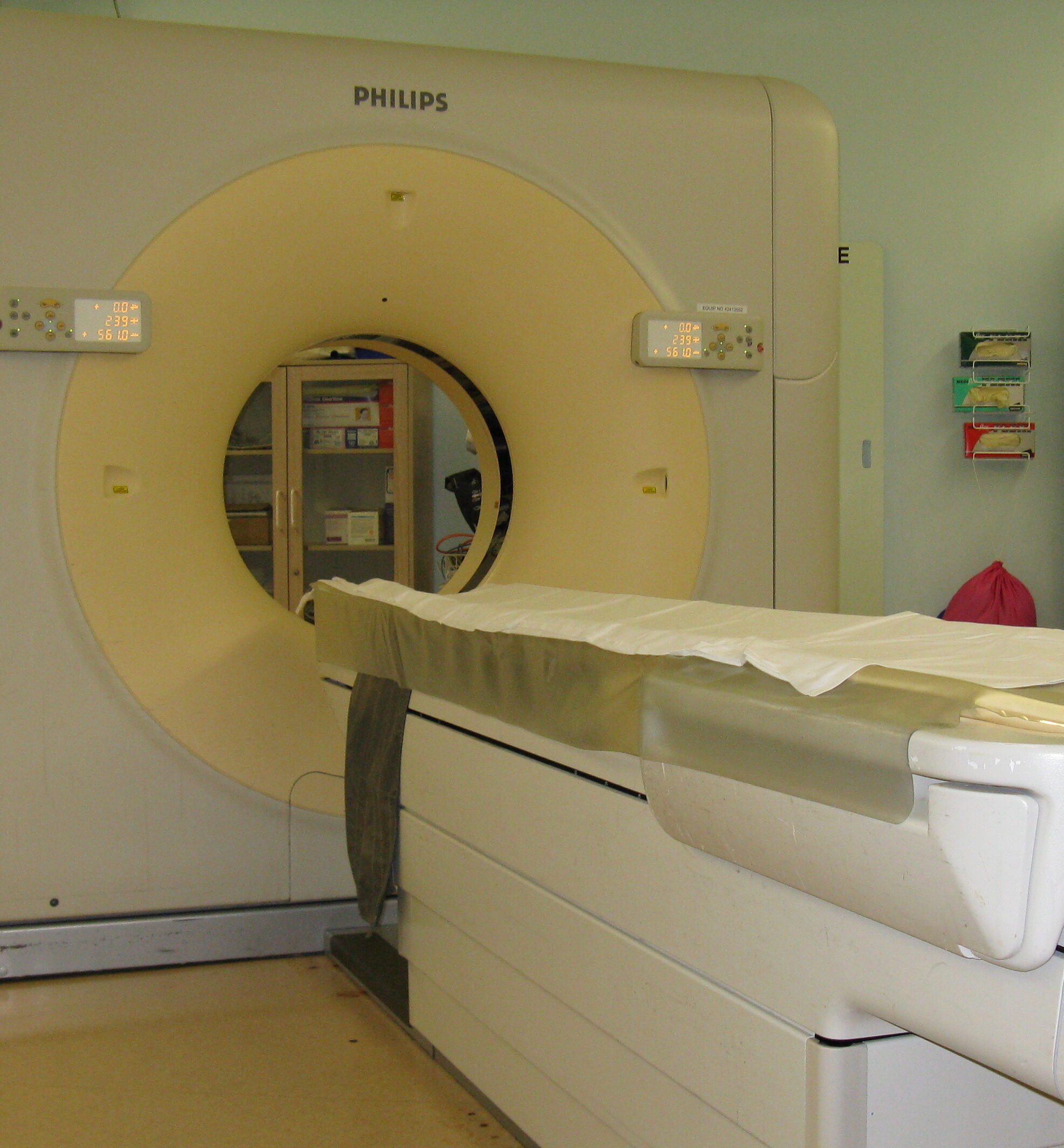

I’m a born librarian — a keeper of books and a maker of records. In fact, I’ve kept a record of all the scans I’ve had since my cancer diagnosis. In part, it’s been a way of reminding myself about all the extra radiation exposure I’m getting with scans. Early-on I was very aware of how that exposure added to my risk going forward, so I asked a friend who is a radiation oncologist about it. He said that, “given the amount of radiation you had for your treatment, the amount of radiation you’re getting in a CT scan is like a drop of water added to the ocean.” At that point, I quit worrying so much.

But, like I said, I’m a born record-keeper. So, I got out my notepad and sharpened my No. 2 pencil and set to work creating my imaging log. The other day, I took a good look at my track record. It’s kind of a grade card, if you will, of my survivorship years.

I totaled it up and in the last 11 years, I’ve had 71 scans. Not all have required radiation exposure, but many have. Eighteen were routine, including my yearly mammogram and periodic DEXA scans to check bone density. Thirty-five of them have been for things not related to cancer. I note that this set of scans includes those needed to check on some symptoms that may be long-term side effects of my treatments — like those for heart issues or for a severely faltering thyroid gland.

But 21 of those scans are a record of how I’ve done with the anxieties of survivorship. Those scans were a result of symptoms I had where I was afraid my luck had run out. In 11 years, that averages out to about one scan every six months. However, only six of the recurrence scares happened in the last six years. The other 15 scares happened in those mythical first five years, when we all anxiously wait to see what side of the percentage divide we’re going to fall into after our treatments.

I know that this is a lot of information to be throwing out there, but I figured I’d use these numbers to tell you that the anxious waiting for the other shoe to drop gets better. Or, I could show you in concrete terms how it has worked for me. And believe me, I’m a real scaredy-cat. I’m not one of those who suffers in silence for months before asking for medical intervention. Just ask my poor, beleaguered doctors!

Learning My Body’s “New Normal”

What I usually realized, after yet another scare had been put to rest with a scan, was that the symptoms I had were a part of learning what was OK and what was abnormal in the “new normal” of my body. Some of the symptoms were just the result of normal aging (though I think that is a suspect category for anyone who has been through much in the way of cancer treatment; the cure ages us in unnatural ways). Some of them were “incidental-omas”, or symptomless signs of possible recurrence found in the process of chasing down other symptoms, like the “mass” on my liver that was discovered and then later disavowed when checking into whether I’d had a heart attack.

I’ve been lucky. No doubt about it. Yet here, at the start of my 12th year of cancer-free (as far as we know) survivorship, the awful awareness that the other shoe could drop at any moment, is just as real as it ever was. In some ways, these feelings are heightened by my success. How much longer can my good luck last? In other ways, they are moderated by more than a decade of experience with hoping for the best yet fearing the worst (and being proven wrong every time).

I think the difference between then and now is that I know my new, post-treatment body better and how it feels. I’ve settled into it, a bit. Plus, I’ve been proven wrong about recurrence so often that I can chuckle about all of it a little more easily than I could five or 10 years ago. I know I’m probably wrong, but … then I smile, feeling a little sheepish at questioning my luck yet again, after all this time.

Still, the awareness that “as far as we know” could change in one blinding moment still haunts me. I have developed blood clotting issues again that I’ve only had once before, in association with my cancer diagnosis. This time, it’s persistent. We can’t get rid of it, so now I’m on blood thinners for the rest of my life. Clotting problems can be an early warning sign of cancer. On top of that, I recently happened to discover that my eosinophils are bouncing around in the very high-normal to mildly bad range, after a lifetime of being solidly in the middle or low-end of the normal range. Eosinophilia can be a sign of cancer.

I know I’m probably wrong, but right now I can only hope and pray that a year or two from now, I’ll be chuckling again. As far as we know, I will.

This post was originally published August 3, 2020, at www.curetoday.com.