With shared decision making on the lips of many in health care conversations these days, I’d like to address five common myths about using shared decision making to make care more patient-centered.

Myth #1:

Face-to-Face Shared Decision Making Is the Goal

Shared decision making is a process where patients and clinicians share information and collaborate to make better health decisions. Clinicians inform patients about their options and the possible outcomes, while patients inform clinicians about how they value the outcomes and what treatments they prefer and why. They generally make a decision together about how to proceed. The goal, however, is not necessarily an in-person shared decision making interaction itself, but better health decisions.

Shared decision making is a process where patients and clinicians share information and collaborate to make better health decisions. Clinicians inform patients about their options and the possible outcomes, while patients inform clinicians about how they value the outcomes and what treatments they prefer and why. They generally make a decision together about how to proceed. The goal, however, is not necessarily an in-person shared decision making interaction itself, but better health decisions.

Shared decision making is a means to that end. The shared decision making process can unfold over time, and not all that time must be spent face to face with a member of the healthcare team. For example, the clinical team may recommend materials about a patient’s options and possible outcomes that a patient may read or view at home, where the insights can be shared more readily with friends or family members. Similarly, a patient can send their responses to these materials electronically through their medical record, where clinicians can study the responses to learn about the patient’s values and preferences. Communication between parties to get to a decision can happen electronically, by telephone, or face to face, to some extent depending on the health consequences of the decision. The result should be a decision where the patient was informed and had their goals and concerns meaningfully reflected in the choice.

Myth #2:

Shared Decision Making Takes Too Much Time

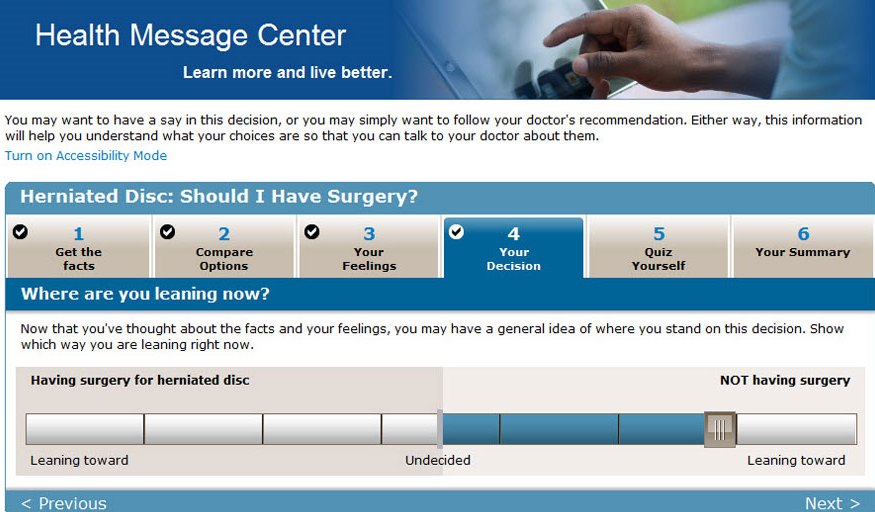

Patient decision aids are tools to help facilitate the shared decision making interaction. Patient decision aids have been shown in many randomized trials to improve the quality of health decisions. When time is limited as it so often is in modern healthcare, decision aids can present the options and outcomes in a standard way, including visual tools such as icon arrays that have been shown to improve the communication of risks. Patient decision aids also include descriptions of the potential health outcomes or value clarification exercises to help patients come to grips with how they feel about outcome states they haven’t experienced, such as temporary or permanent side effects from the treatment. Decision aids can provide summaries of the clinical evidence in a complete, clear and balanced way that may be hard for clinicians to replicate in a brief interaction with a patient.

Some decision aids are designed to be used within face-to-face consultations, others to prepare patients for a provider interaction around a treatment choice. Either way, the International Patient Decision Aids Standards are criteria that can help in the production of high-quality decision aids. Certification standards for patient decision aids are currently being developed by the Washington State Health Care Authority. Decision aids can help make shared decision making practical in the busy world of medical care.

Myth #3:

Most Patients Prefer Not to Participate in Medical Decision Making

Many patients will approach a healthcare decision assuming that there is one right choice for how to proceed, and that the clinician who went to medical or nursing school is the best person to get to the right answer. In truth, many—and perhaps even most—medical problems have more than one medically reasonable way to proceed to establish a diagnosis or embark on treatment. A clinician’s invitation for a patient to participate in a decision under these circumstances may be the most important step in shared decision making.

Research in our network of shared decision making demonstration sites around the country has found that when patients understand that they face a medical decision with multiple reasonable options, the great majority want to participate. And we have found the desire to participate is not influenced by age, gender or level of education. Undoubtedly, some people, and perhaps particularly from specific cultural backgrounds, will still want to defer the final decision to the clinician. However, in that case, the clinician can make the decision in consideration of the patient’s values and preferences, rather than their own. Research has also demonstrated that without a discussion, clinicians do not do well at predicting what patients care most about related to a healthcare decision.

Myth #4:

Few Health Decisions are Appropriate for Shared Decision Making

Shared decision making is often thought about in the context of major, one-time decisions for surgery or cancer treatment. However, shared decision making is also applicable when there is more than one medically reasonable approach. Of course, it’s impractical to go through a detailed shared decision making process for minor decisions. But decisions in the management of chronic disease or prevention are also reasonable candidates for shared decision making.

For example, glycemic targets for diabetes management or the threshold to prescribe a statin medication for primary prevention are both good candidates for shared decision making. The management of chronic conditions often involves a sequence of smaller decisions that should incorporate the patient’s values and preferences to be successful. For instance, taking a shared decision making approach for asthma management has been demonstrated to improve patient-reported and physiologically-measured pulmonary function outcomes.

Myth #5:

Shared Decision Making Conflicts With Guidelines and Quality Measures

If guidelines and their derivative performance measures tell clinicians to do one thing, and informed patients want to do something else, there is a potential for conflict. And both clinicians and patients can feel caught in the middle. In part, this conflict is the result of clinical experts on guideline panels making decisions about the most important outcomes and weighing the harms and benefits of those outcomes without patient input.

When clinicians and patients generally agree that the benefits of an intervention greatly exceed the risks, or vice versa, a “do” or “don’t do” guideline is appropriate. However, when the harms and benefits of an intervention are more balanced, different patients will often weigh these outcomes differently, and shared decision making may be most appropriate.

Recent guidelines for diabetes management, lipid-lowering therapy for high cholesterol, and most (but not all) guidelines for PSA testing have endorsed a shared decision making approach, at least for patients with clinical characteristics that make the decision a “close call.” Well-constructed guidelines, taking into account evidence on patient preferences as well as harms and benefits, can avoid the potential conflict between evidence-based medicine and shared decision making. Knowledge about what informed patients prefer represents evidence in its own right!

Shared decision making is a process to help people make better health decisions. Decision aids can facilitate shared decision making, but are not ends in themselves. When patients they understand why shared decision making is important for a particular decision, the majority do want to participate in their health decisions. Shared decision making is appropriate for many health decisions, including the many decisions involved in chronic condition management. Finally,shared decision making, clinical practice guidelines, and performance measures can be complementary. Getting past myths to the contrary can help create a more patient-centered health system.