Dr. Michael J. Barry’s recent blog post makes an outstanding case for the positive impact of shared decision making and a powerful argument against many myths about it. My thoughts here are complementary and supportive. I am not a clinician. Rather, my perspective is from the vantage point of patients and their families.

My efforts have been to provide health care organizations with the voice of the patient and my research has been to learn more about patient experiences in health care. I’d like to share some of what I’ve learned about patient approaches and preferences related to shared decision making.

Why is Shared Decision Making Important?

A caregiver-patient encounter is the “moment of truth” when care is directly delivered (this does not have to be face-to-face). However, in order for health care organizations to create value with patients, interactions require the resolution of dual-sided information asymmetry (a condition when neither side has all the information necessary to design an optimal plan of care). When a provider (physician) contributes technical (clinical) knowledge and a patient shares personal knowledge, each side obtains the knowledge necessary to work together effectively. Thus, shared decision making exists when a provider and a patient engage in learning with the aim of working together to attain realistic goals for improved health and well-being.

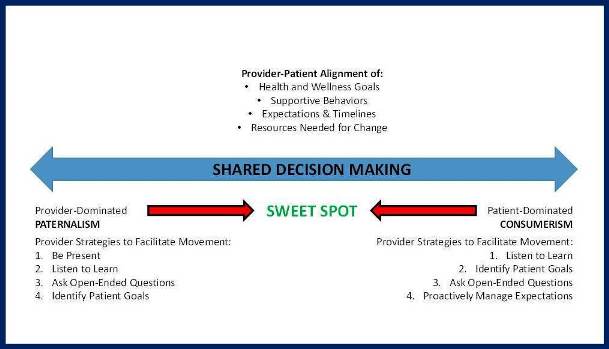

In health care, patients may provide perspective on issues such as tolerance for risk, likelihood to change, knowledge of disease state and possible treatments and preference for treatment. Physician communication with patients conveys critical clinical information, views on treatment alternatives and additional resources for the patient. A continuum of provider-patient interactions is useful to assess the (im)balance of power between provider and customer.

Paternalism, a condition when the physician takes control of the encounter, is quite common in health care. This condition is often provider- or productivity-focused. Paternalism should be tempered with benevolence, to avoid violations of ethical standards. The risk in this type of interaction is that patients may not become fully empowered or engaged to take increasing control of their health and well-being because they are not included in co-designing a plan of action.

Consumerism, a condition when the patient has most control over the encounter, is not the most fertile ground for shared decision making, as it represents a state that may be focused on unrealistic customer demands rather than the patient’s health and well-being. Examples of this include when patients are drug-seeking, are resolute about knowledge obtained from an unreliable source of information or ask for a specific medication seen on TV – situations that may be misaligned with patient goals. Moreover, consumerism in health care can have destructive effects through excessive resource utilization and lack of cost control.

Finally, Mutualism, the condition when patient control is balanced with physician control, presents a state where value co-creation is most likely to be fully realized. When providers acknowledge the contributions of the patient and when patients fully enact their role (e.g., ask questions, clarify issues, and contribute their emotional resources), fertile ground exists for shared decision making to flourish. Mutualism is respectful and transformational. It resolves dual-sided knowledge asymmetry and is tied to optimization of processes, plans, and outcomes. Empirical work has shown that respectful, balanced discourse between physicians and patients results in improved health and well-being, including improved mental health (Kawachi and Berkman 2001), decreased mortality and morbidity (Stewart 1995), increased compliance/adherence (DiMatteo et al. 2002), and cost reductions (Carman et al. 2013).

What Influences where Patients Land on the Spectrum?

Some of the factors that may push providers and patients to either end of the continuum include:

- Cultural factors: Some cultures are more comfortable listening than talking and concede power to providers.

- Generational factors: Older patients may have been raised to avoid questioning doctors, while many younger patients want to know everything before proceeding.

- Educational factors: Patients who are less health literate may avoid exposing themselves by remaining quiet.

- Vulnerability: Patients who feel vulnerable or exposed to a system they don’t understand may react by holding back.

Build a Care Circle

To mitigate these factors, it may be helpful to engage a variety of people within a patient’s family and social network, include translators or other patient advocates in discussions, ask “safe” questions that don’t put patients on the spot and check-in with the patient for understanding on a regular basis.

Finally, the figure lists some strategies that health care providers can consider to move interactions toward the “sweet spot” of shared decision making. These are couched as provider strategies since health care organizations are hosts to visiting patients and as such should endeavor to welcome all who enter.

In general, these strategies include:

- Being focused on the present moment as a sacred opportunity

- Listening to what patients and families are saying not what providers think they will say

- Asking situational questions that help open up patients to additional considerations

- Providing information when and where it is needed.

Patients who prefer consumerism or paternalism aren’t “wrong” – they are simply defaulting to a position based on complex factors. Providers should work to understand motivational factors to help patients manage and reset expectations

Create a Shared Set of Goals

The most important issues for patients are their health and well-being GOALS. Often, patients are in the process of (re)defining these, of understanding a new meaning of health and well-being and coming to terms as to what it will take. I have often heard physicians advise patients to [choose one: lose weight, exercise more, eat better, etc.], only to have the patient share with me outside the exam room that they won’t/can’t follow orders. What a shame! If only the conversation between provider and patient mitigated dual-sided information asymmetry and a common, realistic and scientifically-justified goal was crafted by both sides, there would be a real chance of improved health and well-being.